If we take the point of view that any combination of structures “infinite form of the verb, oriented to the subject as its subject of the action + preceding infinite form of the element fulfilling the function of mediation of the tie between the subject and such form ”, forms single part of the sentence (and the consistency in the principles of description of language phenomena requires this), then complex predicate can include a number of constructions, which are not often acknowledged as such.

Depending on morphological nature of complicating element one can distinguish three types of complication:

1. Active- verbal complication

2. Passive-verbal complication

3. Adjective complication

In the first two types the complicating element is verb, accordingly in the form of active and passive voice, and in the third type it is adjective (also participle, the word of category of state) with the copula verb. Semantic parallelism finds out structural difference of complication of three types comp.:

Не may соте.— Не is expected to come. —He is likely to come.

Traditional terminology of the name of copula is assigned to the verb to be and the verbs of the type to seem, to look an so on, which come forth as mediation link between the subject and the nominal part of the predicate, which expresses the feature. But the similar function is carried out by modal verbs as a part of complex predicate, setting connection between the subject and the feature (here it possesses the nature of action) expressed by infinite form.

Taking into account the differences in semantics of complicating element, one can distinguish several types of active- verbal complication (we shall call them according to the content of complicating element):

1. Modal characteristics of connection of action with the subject

The predicates of this type include modal verbs (can, may, mast and so on) or verb with modal meaning (for example, to be, to have) as complicating element plus infinitive:

'Не can swim like a fish.' (D. Lessing)- U huddi baliqqa o’hshab suzadi

'He must come back.1 (D. C. Doyle)- U qaytib kelishi kerak

'It has to be right.' (H. E. Bates)- Bu narsa to’g’ri bo’lishi kerak.

2. Aspectual characteristics of action

Complicating element designates the stage of the development of action (the beginning, the continuation, the end), its regularity: to begin, to proceed, to quit, to keep on and so on:

She started to walk along the shingle.1 (I. Murdoch)- U dengiz yoqalab yurishni boshladi.

'His heart stopped beating.' (J. Galsworthy)- Uning yuragi urishdan to’htadi.

3. Probability of action

The number of verbs with the meaning of probability, outward appearance of action is very limited (to seem, to appear). For example:

'He seemed to have lost all power of will ' (S. Maugham) U o’zidagi kuchni butunlay yo’qotganga uhshardi.

'They didn't appear to be тоving.' (I. Murdoch)- Ular harakat qilmaydiganga uhshardilar.

4. Expectancy of action

As a result of assigning the appropriate element of complicating the action, designated by the main semantic element of the predicate to the structure of the predicate, it is imagined as accidental, but normally not expected and that’s why unexpected or on the contrary as expected, as natural feature of the object. The complicating element is the verbs like to happen and to prove. For example:

But my memory happened to have tricked me.' (C. P. Snow)- Lekin mening hotiram menga pand berdi.

'It turned out to be Sam.’ (P. Abrahams)- U Sem bo’lib chiqdi.

5. Attitude of the subject to the action

Complicating elements of the predicate denote desire/ unwillingness, intention (to want, to wish, to intend and so on)

I dоn't wish to leave my mother.' (O. Wilde) Onamni tashlab ketishni istamayman.

I should hate to hurt him,' she said.' (I. Murdoch)- Men unga yomonlik qilishdan hazar qilaman.

For the hybrid, verbal-nominal, nature of the infinitive stipulates the possibility of its use, among other nominal functions, and in the function of the object, and the verbs like to want can be directly-transitive single-objective, the necessity to substantiate the given above interpretation of the word combinations like «to want/to wish + infinitive» as a complex predicate but not as the combination of the verb-predicate with the object.

Consideration of to write (in want to write) as an object cannot be excluded as something wrong. Such kind of interpretation of the functions of the infinitive is principally possible. In scientific analyses of phenomena of the language different interpretations of one and the same phenomena are possible and even appropriate. Divergence of this kind is explained by the difference of initial theoretical reference, the fact of depicting the language in the context of different systems, possibility of different procedures of analyses and methods of depicting the phenomena. Diversity of approaches will allow to study and reflect its properties in scientific transformations fully and in details. “There is not and there will not be a single “correct” description of English language”, wrote G. Sledd. Possibility of various approaches makes unanimity of methods especially urgent within the frameworks of chosen system of description. Eclecticism of the methods and hence, the criteria gives distorted picture of the structure of the language as a result, in which existing in reality distribution of the phenomena in its systems is destroyed

Such kind of displacement of the phenomenon from the system, it belongs to by its nature, into the system, alien to it, is intrinsic to the interpretation of the word combinations like (I) want/wish to write as the combination verb-predicate with the object in those systems of describing grammatical structure of English language, in which the formations like (I) сап write and so on are considered as a predicate. Such kind of understanding is generally accepted and does not require any proof. Predicative status of can write is determined by the fact of correlation of action, expressed by the infinitive with the subject, by their subjective- process relations. This tie is set through the verb in infinite form.

The role of the verb in infinite form is not added up to the expression of grammatical meanings and relations. Can and other complicating elements are also the bearers of corporeal meaning. This kind feature is typical to the verb to want. The difference between сап in (I) can write and want in (I) want to write lies in the field of content and in the belonging of appropriate meanings to various semantic spheres. But syntactically the roles of these verbs are the same.

In the realization of the verb (I) want to write and (I) want a book there are two different meanings, connected with the differences of syntactical encirclement. Orientation to the object is intrinsic to the verb want in (I) want a book, having objective character, and verbal orientation of want in (I) want to write. This difference is clearly manifested, if to contrast the verb want (a book) to the other verb, semantically close to it.

Comp.:

'They burned to tell everybody, to describe, to — well — to boast their doll's house before the school bell rang.' (K. Mansfield).- Ular darsga qo’ng’iroq chalinishdan avval o’zlarining qo’g’irchoq uylari haqida hammaga to’g’rirog’ uni tasvirlab berishga sabrilari chidamsdi.

It is unlikely that someone will maintain the fact of presence of, in this case (burn to tell) the verb and the object. Want to tell is different from burn to tell only lexically, in particular, by the degree of intensity of expressing feature. But syntactically, i.e. according to the character of interrelations of verbs and the character of their connections with the subject , want to tell and burn to tell are identical.

6. Reality of the action

A number of complicating elements deny (to feign, to pretend, to fail) or affirm (to manage, to contrive) the reality of the action, denoted by the infinitive that follows such verb: 'Andrew affected to read the slip.' (A. J. Cronin) 'She managed to conceal her distress from Felicity.' (I. Murdoch)

7. The implementation of the action

Such verbs as to try, to attempt, to endeavour, and so on ('Не tried to formulate.' (W. Golding) 'I have sought, primarily, indeed to emphasise how much is involved in 'knowing' a language, [...]' (R. Quirk), have that general component of meaning, which can be marked as “the possibility of implementation of the action”. The reality of actions that they introduce can be positive and negative: I tried to formulate can be equally applied to both the situation I formulated and to the situation I did not formulate. Here is the difference from the complicating elements, considered in (6) where each element allows only monosemantic interpretation and accordingly the transformation of the sentence: ‘I pretended to fall over.' (W. Golding) → I did not fall over, 'She managed to conceal her distress from Felicity.' (I. Murdoch) → She concealed her distress from Felicity.

8. Positional characteristics of the action.

Original type of complication is adding the verbs, denoting state or movement of the subject in the space to the predicate group (to sit, to stand, to lie, to go). The main element has the form of participle. For example:

'Tim stood fumbling for his keys.' (I. Murdoch) 'Adèle came running up again.' (C. Brontë) The first complicating element is weakened in its lexical meaning. Its well-known desemantization is especially vivid in the cases of displacement of the verbs in the group of predicate, which are normally incompatible. 'Oh-h! Just imagine being able to go walking and swiттing again.' (D. Cusack)

Complicated predicate of the considered type has a homonym in the structure of the language as the combination of the verb- predicate with the participle of present tense in the function of modifier of manner. The difference of the constructions is signaled by super-segment means, and especially by the type of joint between infinite form of the verb and participle, comp.: 'She stood touching her face anxiously.' (D. Lessing) and 'Ma stood, looking up and down.' (K. Mansfield)

Another distinctive moment is incapability of the complicating element (due to weakening its lexical semantics) to be modified by adverbials. At the same time the presence of modifying words is normal for meaningful independent verb. Comp.: ‘I sat looking at the carpet.’ (I. Murdoch) и She sat for some time in her bedroom, thinking hard. (I. Murdoch)

One can suppose that for the bearer of the language the second component in complex predicate is semantically central, i.e. in the sentence Не stood fumbling for his keys the main information is — He fumbled for his keys, not Не stood.

Within the limits of single predicate the combination of several complicating elements is possible. Such kind of complication can be called as consistent one:

I shall have to begin to practice’ (K. Mansfield)

In away I had been hatched there, feathered there, and wanted dearly tо

gо on growing there.' (A. E. Coppard)

I can't begin to accept that as a basis for a decision.' (C. P. Snow)

Detail study of combinatory of consistent active-verbal complication will allow to set undoubtedly existing structural regularity in this field. They are revealed particularly in a number of limitations of the combinability of complicating elements. Thus, due to the absence of infinite forms of modal verbs, they cannot be placed after any of the complicating element, they can only begin the line. In non-initial position the appropriate meanings can be transformed with the equivalents of the modal verbs: 'We тight havе to wait/ I said. (C. P. Snow) In other cases combinability is less real according to semantic motives for example: affect to chance or *begin to happen (happen как as a complicating element with the meaning of expectancy of the action). In forecasting semantically impossible constructions it is important to have maximal caution, taking into account the intuition of the bearer of the language, because regularity of the combinability of meanings in most cases ideo-ethnical; compare such constructions, as 'At that moment I соиldn't seem to remember the story, [...]' (T. Capote) 'Poor Tom used to have to prescribe for my father.' (C. P. Snow) and so on. The number of complicating elements in consistent complication is usually limited to two. On the whole consistent complication has not been thoroughly studied yet.

Passive- verbal complication gives as a result the predicate of the structure Vpassen {toV | ingV}, where Vpass — the verb of passive –verbal complication, for example: She was supposed to write a paper on the subject. The bell was heard to r i n g/r i n g i n g. The most important foundation for the interpretation of distinguished constructions as a single member of the sentence and mainly of the complex predicate is their structural and semantic correlation with the predicate of the active-verbal complication (comp.: No component of the theory is allowed to remain — No component of the theory may remain; Mr. Quiason is expected to arrive today — Mr. Qutason must/ may arrive today and so on), whose predicative status has never been disputed by anybody. As in the case of the predicate of active-verbal complication, infinite form of the predicates of passive-verbal complication denotes the action, done by the subject. Finite form grammatically carries out the function of expression of predicativity, and semantically it introduces modifying moment in the character of the connection between the action and its bearer. Most of passive- complicating elements of the predicate (is said/ supposed/expected and so on) can be characterized as the bearers of the meaning of weak modality, if to classify modality of modal verbs (comp. may, must and so on) as strong one.

One can establish four main structural- semantic groups of passive –verbal complicators:

а) verbs denoting the processes of mental activity (to be supposed /believed/known and so on)

They are intended to be the day schools equivalent of the residential houses at boarding schools. (R. Pedley);

б) verbs, denoting communicative process (to be reported/said and so on) 'Repentence is said to be its cure, sir.' (C. Bronte);

в) verbs, denoting the processes of physical perception (to be heard/seen and so on): Distantly from the school the two fifteen bell was heard ringing. (I. Murdoch);

г) «provocative» verbs, i.e. verbs, denoting such actions, which have the action of the subject of the sentence as a consequence (to be forced / made / pressed and so on):

In order to explain these data, we have been forced to develop a number of theoretical concepts and new field procedures. (K. L. Pike)

Adjectives can also be complicating element with the combination of the verb to be or its equivalents. Such kind of complications is called adjective one.

There can be distinguished a number of varieties among the constructions of adjective- complication, which are different from each other by structural peculiarities and semantically:

1) predicate with complicating element, transforming modal evaluation of possibility or authenticity of the connection of the subject and the action. As an adjective element here is used such adjectives as sure, certain, likely and so on: 'Everything is sure to be there.' (E. M. Forster) Later they thought he was certain to die. (P. Abrahams) Т. Н.Huxley's invention, 'agnostic', is likely to be more e n d и r i n g. (J. Moore)

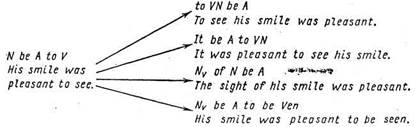

he sentences with the predicate with the complicating element of the given type is characterized by the possibility of application of transformation of nominalization to them N be A to V → Nv be A (He was certain to come → His coming was certain), and also transformation N be A to V → It be A that N V (He was certain to come → It was certain that he would come).

2) The predicates with the complicating elements, denoting physical, psychological or other characteristics of the subject, which is put in the relation with the action, designated by the infinitive.

The circle of lexical units, used as a complicating element here is wider than that in the previous group. The difference in their semantics, correlating with the definite structural differences, can serve as a base for further articulation of the material:

а) Content part of the complicating element denotes capability, necessity, possibility (for the subject) to commit the action. These are the adjectives like able/unable, capable, free, welcome, bound:

Then she would be able to enjoy holiday in peace. (I. Murdoch)

'This flirtation is bound to end pretty soon.' (I. Murdoch)

It is clearly seen the correlation with the group of modal characteristics of active-verbal complication.

b) Content element of complication names the psychic characteristics, expressing attitude of the subject to the action: glad, sorry, ashamed and many others:

Dr. Kroll will be happy to show you the hospital itself later.' (D, Lessing)

She was eager to tell me. (C. P. Snow)

Моr was relieved to be with him for a moment. (I. Murdoch)

The differences of morphological nature of content element of complicator (adjective and participle) determine the participation of the sentences with appropriate predicates in the series of equivalent transformations (1) and (2):

(1) N be A to V → to V make N A → It make N A to V He was happy to come. → To come made him happy. → It made him happy to come.

(2) N be Vl en to V2 → to V2 Vl N → It V1 N to V2 He was amazed to see that. → To see that amazed him. → It amazed him to see that.

c) Adjectives as a part of complication in the given group denotes an objective feature, typical to the subject in the relation with the action named by the infinitive. As a complicating element come forward such adjectives as quick, slow, fit, apt, ready:

He was quick to seize on this unexpected gesture of friendliness [...] (H. E. Bates) [...]

I was slow to pick up the reference. (C. P. Snow)

You weren't fit to take it,' she said. (C. P. Snow)

The boundary between the groups b) and c) is not absolute and appropriate difference is not always manifested. For example, in the sentence But only now I was prepared to listen. (D. Lessing) prepared can be considered both as a denoting position, taken by the subject in the relation to the action expressed by the infinitive and as objective feature of relation, existing between the subject and the action.

d) Content element of complication — adjective expressing (in subjective interpretation of the author of utterance) feature typical to the subject in the relation with the action that it does: stupid, wise, mad, cruel, right, wrong, good and so on:

You are quite right never to read such nonsense.

He had been wrong to let the boy get away.

You have been cruel to me to go away.

Distinctive feature of the constructions that belong to this group is the possibility of the following transformational formations: N be A to V → to V be A p N → It be A p N to V. He was mad to come. → To come was mad of him. → It was mad of him to come.

e) The structures, combined in this subgroup, outwardly coincide with those, which were considered above. But there is difference of semantic structure, which are clearly seen in transformational level of analyses, for example:

Lost dogs are dreadful to think about. (J. Galsworthy)

She was good to look at in a broad way. (P. Abrahams)

Implicit meaning is peculiar to the components of the construction(the subject and the infinitive) : for the first one — object, for the second one :— passiveness, that determine the peculiarities of transformational constructions which differ from depicted above:

Verbal and adjective complications can be combined:

Moira seemed not to be able to move. (D. Lessing)

The first words may be more difficult to memorise than later ones.

(K. L. Pike)

C H A P T E R II

The ways and problems of translating predicate from English into Uzbek.

1.2 The link-verbs in English and their translation into Uzbek and Russian

In shaping the predicate the differences of language systems become apparent stronger and multilaterally than in shaping the subject. This is stipulated by the capacity and importance of the given part of the sentence.[5] Actually, the predicate bears greater number of grammatical relations than the subject does.

The object itself, about which we are talking can reveal itself i.e. determine itself really only through actions and functions which are expressed by the predicate. The predicate connects the doer with the object and the modifiers of the action. That is why the predicate is factual center, which gravitates and gathers subgroups of all parts of the sentence.

This happens in any language. But it is vividly seen in English, where one cannot omit any main parts of the sentence. Here it is indicative to compare Uzbek and English composite nominal predicate.

Mening akam - muhandis. - My brother is an engineer.

The predicate can be expressed by two types of verbs: verbs denoting action, and the verbs denoting existence and objective reality. The use of the verbs of the first group as a predicate does not differ greatly form the appropriate Uzbek verbs of action, that’s why we shall not stop at the predicate, expressed by the verb of action. We shall consider the verbs of the second group, which includes to be and to have, in the meaning and use of which it is observed essential divergence in comparison with the appropriate Uzbek bo’moq and ega bo’lmoq.

1. Verb to be

English verb to be corresponds to Uzbek verb ‘bo’moq’. In its main meaning ‘bor bo’moq’ as it is well-known, verb ‘ bo’moq’ is used in the past and future tenses, but in present tense it is usually omitted. But in English it is obligatory to use the copula verb in the present tense too. Compare the senetences:

Men honada edim.- I was in the room.

Men honada bo’laman.- I’ll be in the room.

Men honada. – I am in the room.

Except the present tense (omitting copula verb in Uzbek and its obligatory presence in English – generally, it is formal circumstance, connected with the different structure of two languages), here the use and the meaning of ‘to be’ coincide with ‘bo’lmoq’ too. But the similarity exhausts here. Verb ‘to be’ is much richer in its potential semantic possibilities than Uzbek ‘bo’lmoq’. Thus, depending on the context, it can obtain the meaning ‘the state in the space’, for example:

The book is on the table- Kitob stolda yotibdi. -Книга лежит на столе..

The table is in the middle of the room- Stol hona o’rtasida turibdi.- Стол стоит посреди комнаты.

The picture is on the wall- Sur’at devorda osilib turibdi.- Картина висит на стене.

Let’s look at some more important of its numerous meanings:

1. “bo’lmoq, qatnashmoq”

She’ll be here all the day- U bu yerda butun kun davomida bo’ladi.

Kitty was here for the holidays.- Kiti bu yerga ta’til payti kelgan edi.

John was at the meeting, too. – Jon ham majlisda qatnashdi.

2. ‘ sodir bo’lmoq, bor bo’lmoq’

It was only last year.- But faqat o’tgan yili sodir bo’lgan edi.

3. ‘teng bo’lmoq, tashkil etmoq’

Twice two is four.- Ikki kara ikki to’rtga teng.

4. ‘turadi (narxlar haqida)’

How much is the hat? – Bu shlyapa qancha turadi?

5. 'iborat bo’lmoq'

The trouble was we did not know her address.- Muammo shundan iborat ediki biz uning manzilgohini bilmagan edik.- Беда состояла в том, что мы не знали ее адреса.

In prefect forms to be acquires the meaning ‘tashrif buyurmoq, borib turmoq’

I hear you've been to Switzerland this summer. – Mening eshitishimcha sen Shvetsariyaga borib kelibsan. -Я слышал, вы ездили в Швейцарию летом.

Has anyone been?- Kimdir kelgan edimi?- Кто-нибудь заходил?

I've been for a walk. – Men sayr qilib kelgan edim-Я прогулялся.

The verb to be in definite word combinations can acquire other meanings too:

Mr Black and Mr White were at school together when they were boys.- Janob Blek va Janob Uaytlar bolaliklarida bitta maktabda o’qishgan.- В детстве м-р Блэк и м-р Уайт учились в одной школе.

Are the boys in bed? –Bolalar uhlashayaptimi?-Мальчики спят?

In English a number of stable combinations with the verb to be were formed, which are translated into Uzbek and Russian as a rule by the combinations of the verbs of action. For example:

Не was ill at ease. – U uzini noqulay his qilardi.-Он чувствовал себя неловко.

Are you in earnest? –Siz jiddiy gapirayapsizmi?-Вы говорите серьезно?

Yossarian was as bad at shooting skeet as he was at gambling. He could never win money gambling either. Even when he cheated he couldn't win, because the people he cheated against were always better at cheating too. –Iossaryan huddi qartalarda uynaganidek likopchalarni ham yomon nishonga olardi. U hech qachon yuta olmasdi, hattoki qalloblik qilgan taqdirda ham, chunki u aldashga uringan odamlar, qalloblik bo’yicha undan ustun edilar.- Иоссарьян так же плохо стрелял по тарелкам, как и играл в карты. Ему никогда не удавалось выиграть. Он не мог выиграть, даже когда мошенничал, потому что люди, которых он пытался обмануть, превосходили его и в мошенничестве.

In these last combinations to be loses its independent meaning keeping only the function of copula verb. This happens in all composite nominal predicates, expressed by the combination of the verb ‘to be+ noun/ adjective/ postposition’ and so on.

Let’s stop in our statement at some word combinations with the verb to be, omitting word combinations of to be with nouns like he is a turner, the task is easy and so оn, which have been spoken enough about in the grammar of English language and which do not represent any difficulty for mastering, for they have little difference from the appropriate Uzbek and Russian word combinations. We shall pay attention to individual word combinations with to be, particularly characteristic to English language and that’s why they are of special interest for us. It is well-known, what meaning the postpositions possess in English. With the help of postpositions, which join a number of more often used English verbs, which enter the main vocabulary fund (to do, to go, to come, to make, to put, to give, to take and so on), the verbs with new meanings are formed. But when adding the postposition to the verbs of action the meaning of initial verb in the combination is either kept equally with the meaning of the added postposition, or the formed word combination acquires idiomatic meaning, and when adding the postposition to the verb to be the main semantic burden is carried by the postposition. For example:

Is Mr Brown in? – Janob Braun uydalarmi?-М-р Браун дома?

No, he is out.- Yo’q u chiqib ketdilar- Нет, его нет. (Он вышел.)

Mr Brown is away at present. – Hozir Janob Braun safarda.- В настоящее время м-р Браун в отъезде.

I hear Mr Brown is back. – Eshitishimcha janob Braun qaytib kelganmish- Я слышал, м-р Браун вернулся.

I am through with my work. – Men ishimni tugatdim-Я закончил работу.

Many of these postpositions are polysemantic.

The train is off. – Poezd ketdi.-Поезд ушел.

The meeting was off. Majlis o’tkazilmadi.-Собрание не состоялось.

The lights were on. –Chiroqlar yoqildi.-Свет был включен.

What is on at our cinema?- Kinoteatrda hozir nima ketyapti?- Что идет в нашем кинотеатре?

The children are not up yet. – Bolalar hali turishmadi.-Дети еще не встали.

The prices for foodstuffs were up. – Iste’mol mollari narhi ko’tarildi. -Цены на продовольственные товары повысились.

Your time is up. –Sizga ajratilgan vaqt tugadi.-Ваше время истекло.

Dictionary records a large number of stable word combinations with postpositions: to be about to do smth.- -moqchi (rejalashtirilgan ish harakat)- собираться, намереваться сделать что-л.;

to be up to smth.- boshlab qo’ymoq-замышлять, затевать что-л.;

to be up to smb. – bog’liq bo’lmoq-зависеть от кого-л.,.

to be for (some place) – yo’lga chiqmoq-отправляться, ехать куда-л and so on.

One can notice how wider English to be is used than Uzbek ‘bo’lmoq’ and Russian ‘быть’. This is very evident in a number of cases where Englishmen prefer composite nominal predicate, which consists of copula verb ‘to be’ and an adjective or participle I or II which have the meaning of appropriate verb, to simple verbal predicate. For example:

Still she was hesitant. (instead was hesitating) –U hali ham ikkilanayotgan edi. -Она все еще колебалась.

Не felt that everyone disapproved of Scarlett and was contemptuous of him. (instead contempted him) – U atrofdagilar Skarletni hush ko’rmasliklarini undan esa hazar qilishlarini his qilardi. -Он чувствовал, что все вокруг не одобряют Скарлетт и презирают его.

These visits were disappointing. – Bu tashriflar uni hafsalasini pir qildi.-Эти визиты разочаровывали (ее).

She was shocked and unbelieving. –U dovdirab qoldi va bunga ishonmasdi.-Она была поражена и не верила этому.

Are you insulting, young man? – Siz, yigitcha, meni haqorat qilmoqchimiz?- Вы что, хотите оскорбить меня, молодой человек?

As it is clearly seen from the examples, the combination of the link- verb to be with the adjective or participle I or II is equal to the appropriate verb (ikkilanmoq, hazar qilmoq and etc.), using which we translate the given word combination into Uzbek and Russian.

The usability of this form led to the origin in the speech of such stable word combinations with to be. For example:

I am serious. – Men jiddiy gapiryapman.-Я говорю серьезно.

She was giddy. – Uning boshi aylandi.У нее закружилась голова.

Don't be so literal. – Hamma narsani aytilganday tushinmang.-He понимайте все буквально.

Не was homesick. – U uyini qumsardi.-Он тосковал по дому.

The second, i.e. nominal element of the given type of predicate can be Participle II as well, for example:

She was amazingly well read. – U haddan tashqari ko’p o’qigan edi.- Она была исключительно начитана.

Moreover, fuzzy differentiation of transitive and intransitive verbs broadened the frameworks of using participles II as a part of the second element of the composite nominal predicate, so it has become possible to use in analogous function the participle II of intransitive verbs too, which is found in Uzbek and Russian:

Now, of course, all you gentlemen are well-travelled. – Albatta, janoblar hammalaringiz ko’p syohat qilgansizlar.-Конечно, все вы, джентльмены, много путешествовали.

She is well-connected. – Uning yahshi tanishlari bor. - У нее прекрасные связи.

Не was well-mounted. – Uning yahshi oti bor edi. -У него была прекрасная лошадь.

In spite of the fact that these are passive constructions according to their form, the subject does not designate the object of the action. On should make a slip in speaking that combinations «to be + participle II» from intransitive verbs in the functions of composite nominal predicate are not frequent. Link- verb to be in the combination with the adjective or the participle as a part of composite nominal predicate force out other link- verbs, which are more appropriate by meaning in this or that context: to get, to turn, to grow and so on, which transform dynamics of the action, transmission from one state into another, for example:

She was hot with sudden rage. - Un to’satdan jahli chiqib ketdi. - Ее внезапно охватила ярость.

Rhett's eyes were sharp with interest.- Ret ko’zlarida qiziqish uchqunlari chaqnab ketdi. - В глазах Рета вспыхнул интерес.

He's lived here only since the year we were married. – U bu yerda faqat biz turmush qurganimizdan beri yashamoqda.Он живет здесь лишь с того года, когда мы поженились.

In some cases to be in theses combinations comes with the meaning of the verbs like to keep, to feel and so on:

Suddenly she was sorry for him. – U unga nisbatan achinishni his qildi.- Вдруг она почувствовалажалость к нему.

She was silent a moment.-U bir oz fursat jimlik saqladi.- Она помолчала с минуту.

For a moment she was indignant that he should say other women were prettier, more clever and kind than she. –Bir fursatga u uning boshqa ayollar unga qaraganda go’zalroq, aqilliroq va mehribonroq degan so’zlaridan uzini noqulay sezdi.-На какое-то мгновение она почувствовала негодование оттого, что он сказал, что другие женщины красивее, умнее и добрее ее.

At last we have to stop at the combinations «to be + noun- doer» (player, reader and etc.), formed from the appropriate verb. It transforms constant quality, intrinsic to this man. For example:

Не is a good swimmer. – U yahshi suzadi.-Он хорошо плавает.

What a small eater you are!- Munch ham kam eysan!- Как мало ты ешь!

Stable idiomatic expressions of this type were formed as well:

to be a poor sailor – dengizda uzini yomon his qilmoq- плохо переносить качку на море,

to be a poor correspondent – yozishni yomon ko’rmoq-не любить писать письма,

to be a stranger- biror joyga kamroq borib turmoq- редко бывать где-л.

2. The verb to have

The verb to have like to be is wider according to its meanings then Uzbek verb “ega bo’lmoq” and Russian “иметь”. Potential possibility of action is put in it like the verb to be.

Магу has a pencil in her hand. (together with : Mary is holding a pencil in her hand.) Meri qo’lida qalam ushalb turibdi.-Мэри держит в руке карандаш.

The city has 100,000 inhabitants. -Shahar aholisi 100000 kishini tashkil qiladi.- Население города составляет 100 000 человек.

In such kind of sentences when the subject– acting person is available, the construction ‘there is’ is also possible.

There is a pencil in her hand.

We haven't any coffee in the house. = There isn't any coffee in the house.

However the verb to have can be used not only with the subject, expressed by the noun, denoting person (the meaning of the verb itself – possession- presupposes it), but it can be used in relation to the objects too. In such cases its meaning is identical to the meaning of the construction of ‘there is’, and they are interchangeable. For example:

Some houses had quite wide grass round them. = There was quite wide grass round some houses.

Jack's eager conspirator voice seemed very close to his ear, and it had a kind of caress, a sort of embrace. = ...there was a kind of caress, a sort of embrace in Jack's voice.

To have, analogous with the verb to be, though more seldom, is used as a link-verb in composite predicate. This can be seen in such word combinations with nouns as как to have dinner- tushlik qilmoq- обедать, to have a talk –gaplashmoq-поговорить, to have a quarrel- urishib qolmoq- поссориться, to have a rest- dam olmoq- отдыхать, to have a walk –sayr qilmoq-прогуляться, to have a smoke – chekmoq-покурить, to have a good time- vaqtni yahshi o’tkazmoq хорошо провести время and etc. The verb to have loses its main meaning and serves as only indication for using something only once, committing any limited action.

If one looks carefully at these cases of using the verbs to be and to have and takes into account their active presence in English, then he cannot leave it unnoticed the manifestation of systematic peculiarities of English language. Actually, Englishman can say to rest, but he nevertheless prefers complicated form — to have a rest. The main point is that, in any verb, expressing concrete action and reflecting definite qualitative side of the action or state the quantitative side, the very fact of this action is included. Analytical tendency of English generate the aspiration to separate formal expression of general and concrete, qualitative and quantitative side of these actions. And then, naturally the composite predicate with the verb to have and nominal expression of quality (adjective, participle, noun) replaces the concrete verb.

A number of stable word combinations with the verb to have were formed which are translated into Uzbek and Russian with the help of action verbs in English. For example:

She has a perfect command of English. U Ingliz tilini mukammal egalagan.-Она прекрасно владеет английским языком.

I wish you to have a good time. Sizga vaqtingizni yahshi o’tkazishingizni tilayman. -Желаю вам хорошо провести время (повеселиться).

In conclusion we should state that as the verb to be with adjectives, participles, or nouns acquires the meaning of the appropriate verb, so the verb to have in the combination with the noun is often used instead of simple verbal predicate, expressed by the action verb. For example:

But if they were under the impression that they would get any information out of him he had a notion that they were mistaken.- Но если им казалось, что им удастся выудить из него какие-то сведения, то он считал, что они ошибаются.

Не had a longing to smoke. – Uni juda ham chekkisi kelyapti.-Ему страшно хотелось курить.

But this kind of word combinations is less frequent than with the verb to be.

Дата: 2019-05-29, просмотров: 406.